By Donnie Campbell | Photos courtesy Donnie Campbell

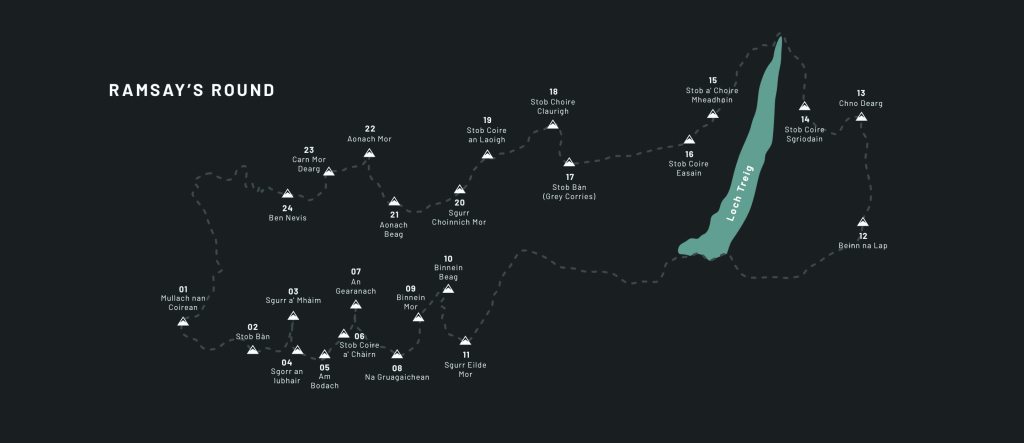

Donnie Campbell is a professional ultra-marathon runner and endurance running coach. In December 2016 he took on Ramsay’s Round; a 24-hour challenge taking in 24 mountains covering 98 kilometres and requiring 8,500 metres of climbing – the equivalent to ascending Mount Everest from sea level.

I’m sat on a frozen rock high up on the Grey Corries, an unforgiving mountain range in the West Highlands of Scotland. It’s taken me 17 hours to climb over 7,000 metres, but I’ve bagged 18 of its 24 mountains – known as Munros in this part of the world. Unfortunately, the nausea has put me off eating, and the vomiting has ensured that my stomach is now empty. My legs are heavy due to the snowy conditions underfoot, while the agony of the Morton’s Neuroma – a type of inflammation of the nerves – is making every step feel like someone stabbing the ball of my foot with a roasting hot iron.

As the sun begins to set, I can see in the distance the six remaining Munros left to climb. Soon it will be dark, and I will be facing another freezing winter’s night in the mountains. My mind begins to wander. How did I end up in this situation?

I have always been able to push myself close to my limits. I don’t know if it’s determination, stubbornness, or simply my ability to suffer yet keep going. I suppose most competitive people will have some of these attributes. But looking back now, I can see I possessed them from an early age. I recall playing Shinty in my teenage years, representing Skye. As horizontal wet sleet teemed down, players were coming off the pitch due to the conditions. But me? I scored four goals in quick succession. This was not down to my skill, but because I was able to thrive in the elements when everyone else was suffering. I guess it was only natural that I’d end up in the Royal Marines…

It was going to take everything I had to get me over the remaining Munros. To complete the Round in under 24 hours, I knew the next few hours were going to be the toughest in my life. I was going to have to dig deeper than ever before, push my physical and mental endurance to the very limits, and boy was it going to hurt. I stood up and set off again, smiling.

My university studies in sports coaching and development allowed me to apply physiological and psychological theory to help me understand how, even as a teenager, I was able to push myself to almost breaking points. To discover the method in the madness, if you like. I’ve always been interested in the power of the mind, and how it can impede or improve physical performance. There is a lot of evidence out there now to suggest that it is the brain that is the limiting factor when it comes to physical performance, not the body.

The ‘Central Governor’ theory, developed by exercise physiologist Tim Noakes, outlines how your brain will cause you to slow down before you reach your physiological max, to protect homeostasis and stop you from physically running yourself to death. Another physiologist, Samuele Marcora, proposes a similar theory; essentially that the brain has the overriding say on how far you are going to be able to push yourself on any given day.

Their conclusions tally up with my experiences. In 2011, I took part in the West Highland Way ultra-marathon: 95 miles between Glasgow and Fort William. With 12 miles to go, I experienced my first ever projectile vomit. My abdominals were in an uncontrollable spasm as a litre of fruit smoothie returned moments after I’d (unwisely) consumed it. It was not pretty, and the thought of calling it quits did cross my mind. But not for long. I shuffled, walked and crawled to the finish line to complete the race in 22 hours 35 minutes. I finished six hours behind the winner.

The next day I could barely walk, but was already planning my next run. I wanted to see how far I could go without sleep: despite my suffering, I sensed that 95 miles was not my limit. The following year I would once again run the West Highland Way, only this time I’d carry on north to the Isle of Skye, a route totaling over 180 miles. My target was to complete it inside 48 hours.

“Beyond the very extreme of fatigue and distress, we may find amounts of ease and power we never dreamed ourselves to own; sources of strength never taxed at all because we never push through the obstruction.”

I first encountered the very meaning of this quote, attributed to 20th Century psychologist William James, 42 hours into my run to Skye. With just over half a marathon to go and one last big climb, I felt a sense of calm come over me and a renewed energy where running felt effortless again. I had previously experienced what people refer to as ‘runner’s flow’, where you feel like you are gliding over the trail or mountains. Sometimes it lasts for minutes, other times a bit longer. But this was different.

I had been fighting against mental and physical fatigue, everything ached, my feet were bruised and battered. But all this seemed to disappear as I found a flow where my pace picked up and my mind – previously occupied with all the pain and fatigue – was now 100% focused on the last few miles. I ran the last half marathon in under two hours, completing the 184 miles in 44 hours and 30 minutes.

What had changed in an instant? What had happened in the last 12 miles to make running seem so easy, when it should have been hard?

In Alex Hutchinson’s book Endure: Mind, Body and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, he looks at human endurance and how, if someone is highly motivated, then they will suffer longer and push their body further to achieve their goal. During that run, I was the most motivated I had ever been. At 4am on the second day, the sun had just risen, and I was running along a road in the middle of nowhere, shouting at myself as loud as I could to keep pushing and maintain my pace: “I HAVE GOT THIS!”, “I CAN DO THIS!”.

An old lady drove past and stopped to ask if I was ok. I told her I was fine, and that I was running to catch the ferry from Mallaig to Skye, prompting her to politely offer me a lift. Even now, I can still see her face contorted with confusion when I declined!

I have always used positive self-talk when exploring my limits of physical and mental performance. It has been shown in numerous studies to increase performance, and is widely accepted in sports psychology as a great coping strategy for when things get tough.

Then there is goal-setting; breaking the run into smaller manageable chunks and focusing on those alone, one at a time. Going into the second night of running to Skye, I divided it into 10km sections, knowing that at the end of each mini-target I would get to see my support team and take on some food and water. But even coping strategies are of little use when things don’t go to plan…

I’m approaching the most technical bit of Ramsay’s Round: traversing an exposed ledge and climbing a steep 30-foot face covered in snow. Support runners Tom and Andrew have come to run alongside me for the last stretch. However, sickness has forced Andrew to bail out after three Munros, and he’s unwittingly taken our micro crampons and head torch batteries back with him. It’s a blow, but I’ve come too far to stop at this point. If necessary, we’ll have to cut steps into the snow with our ice axes and feet. We ascend into the darkness.

Each step, each kick, each ice axe placement has to be perfect. I’ve been on the go for more than 19 hours, but I can’t afford a lapse in concentration here – one wrong foot or hand placement could lead to a fall to almost certain death. Sweat drips off my face from the effort, but as we get over the crux climb, I can see the path leading up toward Munro number 20.

Sometimes, the battle with your mind is one that can’t be won. My first ever DNF (did not finish) came at the Mont Blanc 80km race in 2014. Two weeks before the race I had been suffering from a parasitic infection and had just finished my course of antibiotics before the race. I thought I was 100%. But 15km in I realised this was not the case. As soon as I didn’t feel myself, the negative thoughts cascaded through my brain (“what’s the point of grinding out a finish?”, “why carry on when I know I can’t perform to my best?”). After 30km, I stepped off the trail, handed my number to the marshal and withdrew. As I fought back tears, it proved a far cry from what I imagined my first DNF would look like. It hurt.

Looking back now, it makes sense why it happened. I had lost my motivation, which meant my brain was going to call it quits a lot sooner than when I normally would. I was also planning on asking my girlfriend Rachael to marry me after the race, so I was not 100% focused. Thankfully Rachael said yes, so my first DNF actually turned out to be a great long weekend in Chamonix!

Rachael shares my love for ultra-running, and she is an incredible endurance athlete, one of the toughest I know. We push ourselves and help to motivate each other before and during races. Not long after we got married, she was running a 50-mile trail race when, 20 miles in, she hurt her leg leaping off a rock on a steep downhill. As it progressively got worse, she told me that she had envisaged what I would say: “can you walk on it?”, “can you run on it?”, “keep going then!”. It turned out that she had fractured her fibula. Yet not only did she finish, but she actually won the race. It shows that our motivations to push ourselves, to continue past breaking point, and to endure, can come from a variety of sources and inspirations.

As I stand on Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest mountain, I’ve got just 55 minutes and 1,345 meters of quad-thrashing descent standing between me and a new winter record. I know I can do it. I hurtle down the Ben, trying to stay on my feet through the ice. My heart is pumping, the adrenaline is rushing through my veins, and as rocks kick up off the mountain I keep pushing harder. It’s time to completely empty the tank and hold nothing back.

I splash full speed into River Nevis and seconds later I’m lying crumpled on the finish line tarmac. I have nothing left, unable to respond to those wishing me congratulations. I’ve given it everything I have, I’ve pushed myself to a new limit. And that, for me, is a success. It’s not about breaking records or winning races. It’s about the adventure, the challenge, and exploring my own physical and mental peak.

Donnie completed the Winter Ramsay Round in 23:06, setting a new fastest-known-record.