By Scott Waldrop

For all my adult life, until recently, I’ve been a self-absorbed, somewhat misanthropic, functioning, closet alcoholic. Perhaps the word “closet” is decidedly laughable to those who know me. It’s easy for us to hide in breeding grounds conducive to its concealment, wearing masks such as “musician” and “blue collar worker.”

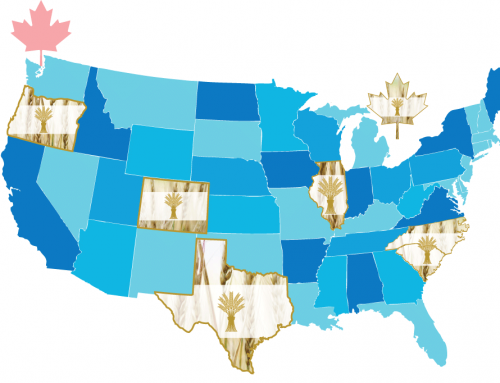

I’ve been sober for about 2 years. This August I ran The Leadville Trail 100, a one hundred-mile race in the heart of The Colorado Rocky Mountains with elevations between 9,200–12,620 feet. In most years, fewer than half the starters complete the race.

Why would I do this?!?

To raise money and awareness for mental illness and addiction – issues which are invariably interconnected and ripple out to affect us all in some fashion. It’s not always The veteran with PTSD or the sexually abused who succumb. The normalization of prescription drugs and wholesale alcohol use leaves unknown multitudes of us in quiet dark places. Most of the time we don’t perceive the gradual slip into the clutches of our addiction until we’re mired prostrate and lost in its sordidness.

It took me nearly 30 years of bloodied limbs and close calls to find myself alone in a derelict parking lot, drinking gut-rot from a paper bag, before even the suggested whisper of the word “alcoholic” bubbled forth from my subconscious. The “A” word seemingly stepped out of my mind, steadfast in its sudden tangibility, and unwaveringly faced me down. I’d known “real” alcoholics or so I thought. They set the “deviant bar” so high that I had nothing to worry about.

So what if I drink crap beer in a coffee mug every afternoon during my drive home from work? It’s not like I live in the woods – or in some dark apartment littered with crack pipes and scattered cat shit all over the floor. For once I took notice of the rare and fleeting realization that I’d built a false narrative to facilitate my behavior. I’d been myopically reciting the same inner monolog since I was thirteen, languishing in a holding pattern of arrested development while circling over some long-since-dead party. I’ve had remarkable luck in that I gleaned this faint insight that would inevitably guide me as I traversed my own way from an adulthood of marinating (at the time I had too much false pride to bear the stigma I thought AA would place upon me). Whoever it was that crouched under the drink was a perfect stranger whose acquaintance terrified me. That I acted at all on this realization is still mysterious to me.

With newfound clarity, I can look back at my disconnect and heartbreak towards friends and loved ones who battled the same issues. Some continue to do so. Moreover, I’ve watched many ultimately lose their fight and currently witness the same pattern run its creeping course with a new cast.

The charity I work with,The Herren Project, provides many people with the treatment they could otherwise never afford – even when they desperately want a way out. It offers them a richly deserved second chance. Giving someone this gift is no less miraculous to them than heeding my epiphany was to me, as those who may be chosen for care are sadly few and far between when it comes to sheer numbers. We strive to end the stigma around addiction and the demonizing of people who are suffering from an illness that has spiraled beyond their control. Those affected are so often good people with hearts of gold – they are mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, our soldiers – limitless in potential but with broken compasses. At my worst I was an obese chain-smoker who would drink to blackout nightly. My little boy begged me to stop but my illness was tenacious in its ability to circumnavigate the heart-wrenching pleas, and excused my recovery unto some arbitrary date that was perpetually in “the near future”. I was on a collision course with a pathetic, tragic and or violent end, and the profound certainty with which I perceived my impending doom was ever surmounting. At this “critical-mass” moment while I floundered in depression, anxiety, and narcissism – I found my way through a successive archipelago of trajectory-changing awakenings (perhaps catalyzed by some teary secular beseeching towards a stranger listener past the blackish 4 am sky).

It’s not lost on me that I’m quite lucky in this regard. Too many of us don’t chance upon this moment of clarity and are counted out as the guy or girl who just can’t “get their shit together”. To abbreviate and spare the airy details – running was integral to my recovery, as many distance runners before me I’ve come to find. The gratitude one feels on the other side of addiction is a compelling force to be sure. My story isn’t terribly unique if you Google things to the effect of “ultra runner addiction.” I’m not adding anything new to the game. I’d simply like to share what I’ve found with others who want to listen – to be another voice in this sea of voices offering words of empowerment and hope. If I can go from 3-day hangovers with heart palpitations to distance running, anyone can. It’s never too late to be brand new… never.