By D.C. Lucchesi

Like most runners, Amanda Mingo has fond memories of her first marathon. It was Chicago in 2000. A big-city marathon with all the bells and whistles: Chicago’s enthusiastic crowds and flat, fast course are favorites of first-timers from all over the world. And Mingo, the reformed smoker–turned-runner, took away more than just the sense of accomplishment from completing the marathon. Along with the many miles logged before race day, she raised thousands of dollars for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society as a member of Team in Training.

“I know I couldn’t have done it without the support and incentive of running for charity,” says Mingo, whose charity marathon experience has kept her running.

Besides the obvious benefits of fundraising, training for an event with a charity team adds immeasurable financial and moral support. Some organizations front the athletes’ travel costs and hotels and provide a literal support group to prepare for the event, from training schedules and group runs to encouragement along the race route.

Running, walking, or riding for a cause has boomed since the days when a shaggy-haired, prosthetic-wearing Terry Fox attempted a cross-Canada run to raise money and awareness for cancer research. The charity athletic business can trace its roots to the March of Dimes efforts to raise money during the polio epidemic decades ago. Organizers agree the events continue to be an effective way to raise money and awareness. USA Track and Field, which keeps tabs on such things, estimates there are more than 11,000 charity events each year raising upward of $1 billion annually for their respective causes.

But the proliferation and popularity of charity athletic events also raises some concerns: More races mean more competition for limited dollars—and athletes. Then there’s the argument that charity athletes are diluting the quality of the events, producing substandard times and limiting the number of open slots in popular events; a point quick to be aimed at exclusive events like Ironman Kona or the Boston Marathon, where charity athletes are not bound by the same qualifying entry standards.

Tim Rhodes’s Run for Your Life and Event Marketing Services, Inc., produces, times and scores more than 40 events annually, many of which are tied to charitable causes. Rhodes says the successful events are ones that have set themselves apart and provided a “hook.” Whether it be an emotional connection or a charitable one, they must provide an experience that enhances rather than detracts from the competitive side of the event.

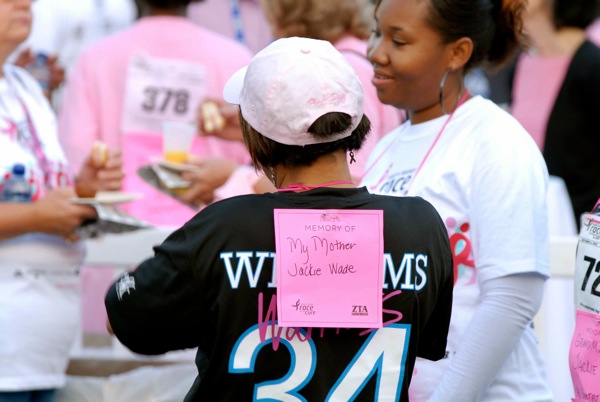

“We do a race, but we’re really here for cancer,” says Rachael McGrath, events coordinator for Charlotte’s Komen Race for the Cure, which had 14,000 participants in 2009.

McGrath says events like these are so successful because people can relate to the cause. The runner may not have breast cancer, but if one in eight women will be diagnosed, there’s a good chance someone they know has—or will. Race for the Cure and the buzz surrounding it also make it easier to talk about something personal like breast health and the importance of examination and early detection.

Big events like Race for the Cure also create ripples beyond fundraising. Their notoriety attracts star power like Carolina Panthers running back D’Angelo Williams, whose mother is a breast cancer survivor. Having Williams on the team got Belk department stores on board and put the message of education and early detection in front of a new audience: the NFL crowd.

“We’re getting the word out,” adds McGrath. “Advancements in breast cancer can affect all types of cancer.”

Training for and completing a marathon, triathlon, or other physical challenge may be somewhat metaphorical to fighting a debilitating disease like cancer. For many athletes, participating with a struggling or lost loved one in mind adds the motivation to persevere. It’s also a way for survivors to celebrate their victory, family and friends to honor loved ones who have passed, and for the rest of us to feel like we’re in some way connected to the effort.

“It blows me away,” says Basil Lyberg, executive director of 24 Hours of Booty. The fundraising cycling event has drawn 6,000 cyclists and raised over $3.7 million for cancer research and education since its inception eight years ago.

“Participating is a way for folks to pick up a shovel and move some dirt,” adds Lyberg. “This gives them a way to feel like they’re doing something, too.”

The American Cancer Society estimates that more than 1.5 million new cancer cases will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year. More than half a million Americans will die from some form of cancer in 2010, making cancer the second leading cause of death in the U.S. The good news is that the survival rate for all cancers is going up. The 5-year relative survival rate was 68% for cancers diagnosed between 1999 and 2005; an increase attributed to progress in earlier detection and improved treatment.

It would be hard to argue that the charity athlete’s contributions, participation, and vision shouldn’t share in that success. Since Terry Fox’s attempt to cross his native Canada, millions of dollars have been raised worldwide in his name through the Terry Fox Foundation, which will produce a run in Raleigh this fall. Similarly, Charlotte-based 24 Hours of Booty has meant millions to the Lance Armstrong Foundation and other local charities and expanded to Columbia, MD, and Atlanta—all from Spencer Lueders’s humble solo effort.

Says Komen’s McGrath, “There can’t be too much awareness and education—or fundraising.”

# # #

D.C. Lucchesi runs himself ragged on the trails and lives to tell (and write) about it on his blog at http://dirtyjokesandstories.blogspot.com. If you’d like to join the fun, email him at dc@runforyourlife.com.