By Anthony Greco

It started with a pinch in the hip. It turned into two months of no running and a palpable fear of never running again.

The pinch was trochanteric bursitis, also called hip bursitis. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons describes it as an inflammation of a bursa around where your leg connects to your hip. Bursa “are small, jelly-like sacs that are located throughout the body,” according to AACS. One doctor described bursa as God’s lubricant. It’s the injury that kept Ryan Hall from running the 2013 ING New York City Marathon and not competing in one until this year’s Boston Marathon.

In media coverage before the NYC race, Hall said, “A long string of very aggressive training has aggravated my hip and it has not been able to fully calm down, such that I don’t think racing on it is wise.”

He made a decision I failed to make. Like a lot of endurance athletes, I stuck to my plan and ran the Jacksonville Bank Marathon in Florida. I woke up the next day in pain with a visibly swollen hip. It was the beginning of a yearlong recovery.

I sought treatment from a physical therapist familiar to these pages, Brian Schiff from the Athletes’ Performance Center with Raleigh Orthopaedic. He said hip bursitis happens when “friction builds up between the iliotibial band and the greater trochanter. It kind of becomes inflamed and gets swollen.”

First the swelling had to be reduced with a cortisone shot. Next was accepting the seriousness of the injury. Successful recovery required deciding to treat recovery with same focus and dedication as marathon training. It worked, as I’ve returned to racing, set a PR and won a race. Building back up took good coaching.

“The day after an injury and subsequent months that pass you are losing fitness so rapidly, and not only fitness but an ability for your muscles to tolerate accumulated fatigue,” says Cliff Scherb, founder of Glucose Advisors, LLC, and TriSTAR Athletes. Scherb is primarily a triathlon coach and leader in diabetes management for athletes of all abilities. “People take time off after an injury and don’t account for the loss of fitness and ability to endure stress. And they shoot right back up to their previous training load. The quick return sets them up for a repeat injury.”

I didn’t want a repeat, so I followed Schiff’s and Scherb’s plans. The first step was listening to Schiff when he told me to take time off and focus on strength training. My problems can be traced to high school. I suffered an injury during lacrosse that sidelined me for a season and caused muscle atrophy in my right leg.

“We’ll see problems in the upper hip as well as at the knee but usually related to some sort of muscle imbalance in terms of either tightness or weakness in the hip,” Schiff said. “You always need unilateral support. A lot of times the ground reaction forces travel up the chain, and if there’s a weakness or imbalance on one side, then over time, as mileage increases, it will manifest” in a pattern of discomfort escalating to a debilitating injury.

That’s exactly what happened to me over three years as I increased my training load chasing faster times.

You ultimately have to treat the source of your injuries. While I benefited from medical treatments in addition to the cortisone shot, I would not have been able to reach new levels such as a lifetime weekly mileage peak this year without treating the underlying weakness.

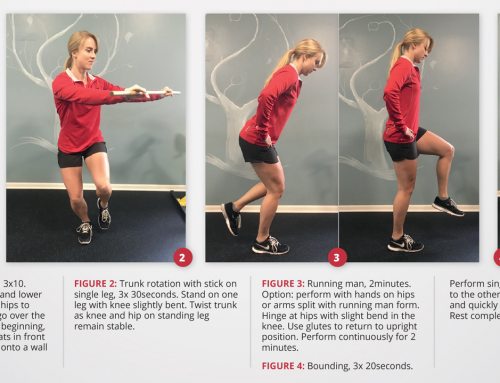

“I’m such a big fan of doing a lot of single-leg work to work on reducing and eliminating imbalances and maximizing the body’s ability to handle its own weight on one limb,” Schiff says. “So when you run it can better stabilize, better absorb the force and of course from a performance standpoint generate force and be efficient to maximize running economy.”

Strength training can be a bore for some endurance athletes, but you have to do those workouts with the same zeal to recover and guard against future injuries. The focus gives me renewed confidence in reaching a lifetime goal of Boston Marathon qualification.

# # #

Anthony Greco is a lifelong athlete who started running seriously in 2004. He ran his first race, a 4-miler, in 2009. Since then he has pushed his 5k PR to 18:06, half-marathon PR to 1:21:31 and marathon PR to 3:11:52. The training process drives him more than results.